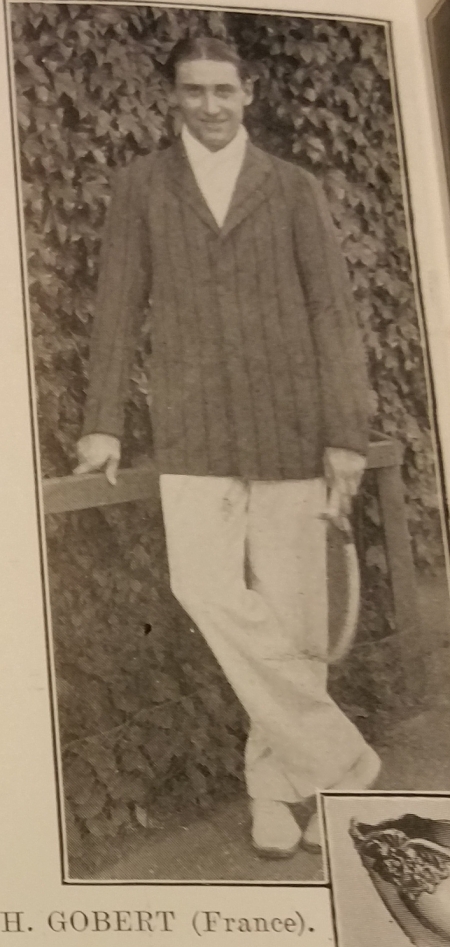

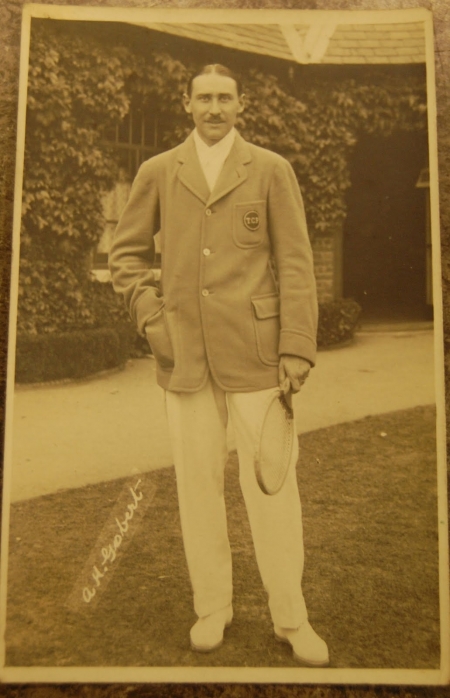

André Maurice Henri

Gobert

Male

France

1890-09-30

Paris, France

1951-12-06

Paris, France

The first piece below was translated and adapted from the Wikipedia entry in French on André Gobert, which can be viewed here:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9_Gobert

André Gobert was born on 30 September 1890 in Paris, to Jean-Baptiste Gobert (1841-1896), a civil engineer and native of Vic-sur-Aisne in Picardy, and Hélène Marie Henriette Gobert (née Desliens; 1848-1903), who was from Paris. André Gobert had one sibling, an older sister called Marie Suzanne (b. 1885). They were orphaned at an early age and subsequently looked after by guardians.

André Gobert attended the Lycée Carnot in Paris and later studied engineering. He first discovered lawn tennis while holidaying in the north-western French coastal town of Cabourg. He later became a member of the Sporting Club of Houlgate, in that coastal town in north-west France and, subsequently, also joined the Racing Club de France and the Tennis Club de France, both located in the French capital.

It was at the Tennis Club de France that André Gobert really learned the basics of lawn tennis, under the tutelage of the American player Leonard Ware. Because it had indoor courts, players were able to practice there throughout the year. As a result, Gobert made rapid progress and became one of France’s top lawn tennis players in the years 1910-14.

In 1913, André Gobert began his military service with the 7th Toul artillery regiment. This meant that he had less time to focus on lawn tennis. During World War One, he served with the French Army as an aeroplane pilot and, reached the rank of lieutenant. For services rendered during the war he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour and an Officer of the Legion of Honour as well as being awarded the War Cross/Croix de Guerre.

On 5 May 1919, in Saint-Pierre-de-Chaillot catholic church in Paris, André Gobert married Estelle Marie Aimée Odette Bourceret (1896-1933), a native of Paris and herself a lawn tennis player. She and André Gobert occasionally took part in the mixed doubles event together. They had one child together, a son called Olivier Jean Gobert (b. 1920), who would also become a lawn tennis player.

After World War One, André Gobert returned to tournament play and enjoyed more success, notably on indoor courts. But his lawn tennis form was never quite as good as it had been before the war, and he turned increasingly to golf. He managed to excel at this latter sport, too, becoming one the best French players, and notably winning the French Amateur Golf Championships in 1927.

André Gobert became an industrialist and was also manager of a textile manufacturing company.

Lawn tennis career

Part I – Indoors

Although adept at playing on the clay courts common in his native France, André Gobert also excelled on the fast grass and indoor wood surfaces. At the British Covered Court Championships, held indoors on wood at the Queen’s Club in London, he won the men’s singles title five times, in 1911, 1912 and again from 1920 to 1922. In the final match in 1912, he notably beat the reigning Wimbledon singles champion the New Zealander Anthony Wilding, in five sets, 3-6, 7-5, 4-6, 6-4, 6-4.

At the French Covered Court Championships, held indoors on wood at the Tennis Club de Paris, where Gobert had learned how to become a champion player, he also won the men’s singles title five times, in 1912 and 1913, and again from 1919 to 1921.

At the World Covered Court Championships tournament of 1919, held at the Sporting Club de Paris in the French capital, André Gobert won the men’s singles title, defeating his compatriot Max Decugis in the final, 6-3, 6-2, 6-2. Gobert won the men’s doubles event at the same tournament with another Frenchman, William Laurentz; in the final they beat Nicolae Mishu of Romania and the Englishman Henry Portlock, 6-1, 6-0, 6-2.

In the indoor lawn tennis events at the Olympic Games of 1912, held in Stockholm, Sweden, André Gobert won the gold medal in the men’s singles event, defeating the Englishman Charles Dixon in the final, 8-6, 6-4, 6-4. Together with Maurice Germot, Gobert also won the gold medal in the men’s double event, beating the Swedes Carl Kempe and Gunnar Setterwall in the final, 4-6, 14-12, 6-2, 6-4.

Part II – Grass

In 1910, André Gobert took part in the Wimbledon tournament for the first time at the age of 19. Although he lost in the first round of the men’s singles event, he won the Wimbledon Plate, an event open to players who had lost in the first or second round of the main men’s singles event. In the final Gobert defeated the Englishman Percival Davson, 6-4, 6-4.

The following year, Gobert and his compatriot, Max Decugis, created history by becoming the first French players to win one of the five main titles at the Wimbledon tournament, when they took the men’s doubles. Having won five matches to reach the All-Comers’ Final, they then defeated the Irishman James Parke and the American Samuel Hardy 6-2, 6-1, 6-2 to reach the Challenge Round where they beat the holders, Anthony Wilding and the Englishman Major Ritchie, in five sets, 9-7, 5-7, 6-3, 2-6, 6-2. In 1912, Max Decugis and André Gobert lost their Wimbledon doubles title when the English pairing of Charles Dixon and Herbert Roper Barrett defeated them in four sets in the Challenge Round.

In 1912, on his third appearance at Wimbledon, the 22-year-old also reached the All-Comers’ Final in the men’s singles event, notably beating players such as the Irishman James Parke, the German Friedrich Wilhelm Rahe and his compatriot Decugis on his way there. In the All-Comers’ Final he was beaten in four sets by the Englishman Arthur Gore, three times former Wimbledon singles champion, 9-7, 2-6, 7-5, 6-1.

Part III – Clay

At the early French National Championships tournament, which was open only to French players and foreign players who were members of a French lawn tennis club, André Gobert won the men’s singles title in 1911, defeating Maruice Germot in the final match, 6-1, 8-6, 7-5. Gobert won the same title for a second time in 1920, when he beat Max Decugis in the final match, 6-1, 3-6, 1-6, 6-2, 6-3. In 1911, Gobert also won the mixed doubles event at this tournament, when he and Marguerite Broquedis beat the defending champions, Édouard Mény de Marangue and Marguerite Mény, who were brother and sister, in the Challenge Round, 6-4, 6-3.

At the second edition of the World Hard Court Championships, held at the Stade Français in Paris in June 1913, André Gobert reached the final of the men’s singles event, where he was beaten by Anthony Wilding, 6-3, 6-1, 1-6, 6-4. In 1920 and 1921, Gobert won the men’s doubles event at the same tournament, both times with William Laurentz. In 1920, they defeated the South African player Cecil Blackbeard and Nicolae Mishu in the final, 6-4, 6-2, 6-1. In 1921, they beat their compatriots Pierre Albarran and Alain Gerbault in a four-set final, 6-4, 6-2, 6-8, 6-2.

Part IV – Davis Cup

André Gobert first represented France in the Davis Cup in 1912. His final win-loss totals in this competition were 2-7 in singles and 1-3 in doubles. Although early French lawn tennis players such as Gobert, Max Decugis and Maurice Germot did not enjoy a great deal of success in the Davis Cup, this is partly because the sport was still developing in France, and partly because most ties were held on unfamiliar grass courts. However, these players were a great inspiration for the French players who came after them, especially the Four Musketeers – Jean Borotra, Jacques Brugnon, Henri Cochet and René Lacoste – who would help France dominate the Davis Cup in the years from 1927 to 1932.

--

The following piece on André Gobert is taken from the book The Art of Lawn Tennis, by the great American lawn tennis player Bill Tilden. The book in question was first published in 1922:

One of the most picturesque figures and delightfully polished tennis games in the world are joined in that volatile, temperamental player, Andre Gobert of France. He is a typically French product, full of finesse, art, and nerve, surrounded by the romance of a wonderful war record of his people in which he bore a magnificent part, yet unstable, erratic, and uncertain. At his best he is invincible. He is the great master of tennis. At his worst he is mediocre. Gobert is at once a delight and a disappointment to a student of tennis.

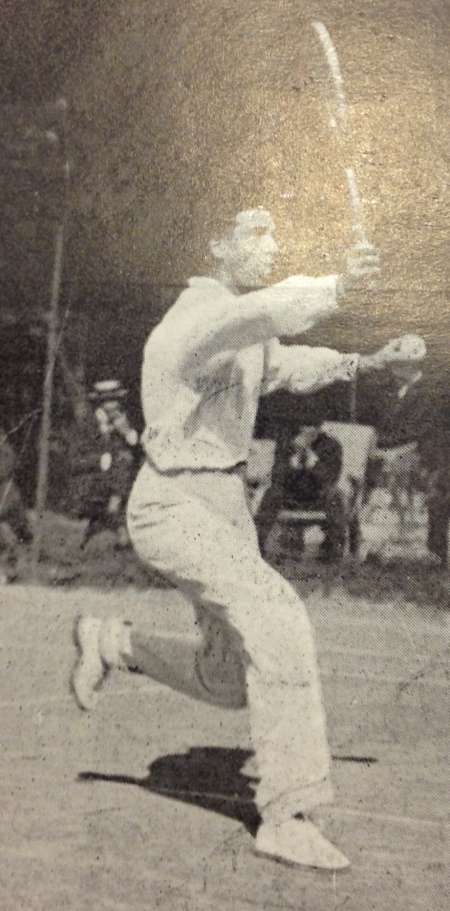

Gobert’s service is marvellous. It is one of the great deliveries of the world. His great height (he is 6 feet 4 inches) and tremendous reach enable him to hit a flat delivery at frightful speed, and still stand an excellent chance of it going in court. He uses very little twist, so the pace is remarkably fast. Yet Gobert lacks confidence in his service. If his opponent handles it successfully Gobert is apt to slow it up and hit it soft, thus throwing away one of the greatest assets.

His ground strokes are hit in beautiful form. Gobert is the exponent of the most perfect form in the world to-day. His swing is the acme of beauty. The whole stroke is perfection. He hits with a flat, slightly topped drive, feet in excellent position, and weight well controlled. It is uniform, backhand and forehand. His volleying is astonishing. He can volley hard or soft, deep or short, straight or angled with equal ease, while his tremendous reach makes him nearly impossible to pass at the net. His overhead is deadly, fast, and accurate, and he kills a lob from anywhere in the court.

Why is not Gobert the greatest tennis player in the world? Personally, I believe it is lack of confidence, a lack of fighting ability when the breaks are against him, and defeat may be his due. It is a peculiar thing in Gobert, for no man is braver than he, as his heroism during the War proved. It is simply lack of tennis confidence. It is an over- abundance of temperament. In victory Gobert is invincible, in defeat he is apt to be almost mediocre.

Gobert is delightful personally. His quick wit and sense of humour always please the tennis public. His courteous manner and genial sportsmanship make him universally popular. His stroke equipment is unsurpassed in the tennis world. I unqualifiedly state that I consider him the most perfect tennis player, as regards strokes and footwork, in the world to-day; but he is, not the greatest player. Victory is the criterion of a match player, and Gobert has not proved himself a great victor.

Gobert is probably the finest indoor player in the world, while he is very great on hard courts; but his grass play is not the equal of many others. I heartily recommend Gobert’s style to all students of the game, and endorse him as a model for strokes.

--

The following piece was written by André Gobert, probably in French, before being translated into English and published in The Windsor Magazine (London/Melbourne), a twice-yearly magazine, in its edition of June-November 1922.

My Lawn Tennis Life

By André Gobert

I was born in Paris, in September 1890. My father died when I was six years old and my mother when I was twelve. My only near relation was my sister, a little older than myself. Every summer, we used to go for our holidays to a little seaside town named Cabourg, situated on the north coast not far from Deauville. There, for the first time in my life, was lent to me when I was eleven years old, a thirteen-ounce tennis racquet belonging to one of my sister’s girlfriends. I was permitted to pick up balls and act as ball-boy for the grandes personnes, who played what I already thought to be a wonderful game.

Of course, the play was really of quite a poor standard, being merely the “pat-ball” game of old times played on a court which probably had not the real proportions. This tennis court was roughly constructed between two walls separating two cottages; the lines, more or less straight and of dark blue colour, were painted on wooden laths so as not to get worn out too quickly. There was hardly any run on the back or side, certainly not two yards; immediately beyond the outside lines the court ended and the grass (and what grass!) touched the outer part of the lines.

The tennis played was of the simplest sort; everyone stood back; it was, by the unwritten law of that antediluvian epoch, almost forbidden to approach the net and volley. Any shot had to be played as near as possible to one of the opponents and if, by transgressing this rule, any of the contestants dared to play a short one or make too hard a hit, it was considered a horrible offence.

A player of such calibre was immediately called a “carottier,” which meant in our cant French, that he did not play the game fairly. I did not miss, of course, any of these memorable séances, and though I was not yet allowed to play, my pleasure was great if I could handle the racquet of any kind person not actually on the court. Between every service game I first sent the balls to the other side of the net with my racquet, and then rushed promptly to pick them up and hand them to the server.

Backhands were quite an unknown thing; everyone tried to run round, and when occasionally, once or twice during the week, anyone had succeeded in sending back a real backhand hit, naturally executed in the most deplorable style, this wonderful fact was a subject of conversation for many days.

How it was that I had such a fancy for the game and loved it to such an extent as to prefer watching it to playing any game suitable to my age with my little friends, I cannot tell. But I really loved to watch it better than I liked doing anything else. This lasted two or three years. Occasionally, I was given the opportunity of practicing a few shots with some very kind person, and when, by an extraordinary piece of good luck, they missed one to complete their foursome, I was permitted to take part in a game. This was great and I remember how quickly my heart beat. Of course, there was no question of my playing during the winter in those years. I had a chance during the month we stayed at Cabourg, but that was all.

In 1905, I think, the Sporting Club of Houlgate, another town three miles from Cabourg, was opened. At that time, I had improved and I played often with my older friends; we did not know yet the benefit of what I would call the “symmetrical grip,” and used to serve and play with the face of the bat parallel to the net, using a kind of push shot, with the head of the racquet always held upwards. The service had, of course, little strength and was nearly always played with backspin.

One day I had an opportunity to go and watch the play at Houlgate. It was a revelation to me, as I saw what I found was quite a different game. A few English and American players, spending their holiday in that delightful resort, played the game with good French players. To me, they seemed to play a wonderful game, driving, volleying, serving at a terrific speed and, to my great astonishment, going for placements! What a change, what a revolution in my mind! Back at home, I told all this to my team-mates and we tried, day after day the “new” shots and the “real” game.

One very lucky thing for me happened that same year. During the winter I was a student at a college in Paris named the Lycée Carnot, where we had a very large space covered with a glass roof, used as a recreation ground for the different classes, and the floor of it was entirely of asphalt. Some of the old students had the excellent idea to ask, and the luck to obtain, per-mission to use it on Thursday and Sunday afternoons, when the lycée was closed, to play tennis.

A collection was made amongst these enthusiasts, and they were able to buy two nets with posts. At the beginning, the lines were marked with chalk; we had to do this ourselves, of course, and it took some time. The posts could not be solidly fixed, as we were not permitted to dig holes in the ground. We had to put weights on the little platform at the base of the posts; every two or three minutes these used to slide on the ground, and the net in consequence lowered itself to such an extent that we had to pull them apart. To complete the appointments, stop nettings were spread between the rails of the balcony at both ends of the courts, to avoid the balls breaking the glasses of the surrounding windows.

This was my first experience on a covered court. Half a dozen good players, most of them old students of the lycée and members of the Racing Club de France or the Stade Français, clubs which had no covered courts, used to come very regularly every Sunday and Thursday. They knew the game, had a good style, an orthodox grip and all the range of strokes. I improved my game tremendously during that winter, playing all the time against better players than myself. Watching my improvements, they gave me much good advice and encouragement and I began to understand that I might some day play decent tennis.

The result was that the next summer, 1906, I found myself a better player at Cabourg, and had no difficulty in playing with the elder players on our private court. In 1907, after some good tennis on our covered court at the Lycée Carnot, I badly wanted to join the Houlgate club, as they had handicaps and championship events reserved to the members of the club. The great difficulty was to convince my guardian – who had charge of me – to give me the necessary sum of money to pay the club’s fee for a fortnight’s membership. I needed thirty francs, a little over a pound at the pre-war rate. After much discussion and the moral help of my sister, I succeeded in raising this enormous amount of money.

I then entered for the members’ championship and handicap singles and lost both in the very first round by two love sets. I played, if my memory is accurate, an Englishman named Bowlen, in the championship. His game, mostly cut or sliced drives and backhands, was a terror to me and I could not hit two balls right. That same year, I played also in the open tournament; being a little more successful, I passed two or three rounds only to meet Bowlen again – the ultimate winner of the cup – who, this time, allowed me five or six games in the two sets. I had improved and understood the benefit of “club tennis”.

I decided to join, as soon as possible, one of the leading Paris clubs and, in the spring of 1908, became a member of the Racing Club de France. My first handicap thereat – the spring meeting for members of the club only – was, by no means, a success: I was on the +15.3-6 mark and failed badly. I played again at Cabourg, and at Houlgate, where I did much better this time and, when autumn arrived, I made my application for the most famous covered court club of the capital, the Tennis Club de Paris. This club was regarded by everyone as the French citadel of high-class tennis, and included among its members all the leading players of France – Max Decugis, Maurice Germot, Paul Aymé, André Vacherot, Édouard Mény, Albert Canet, Jacques Worth, Paul Lebreton, Félix Poulin, Georges Gault, and many other prominent players.

It was at this club that the modern game was played. The sporting as well as the club spirit were very high; everyone played the game for the game itself, with the main idea of improving his tennis. The French style of play was carefully nursed under the keen and paternal eye of the late Mr Armand Masson, one of the founders of the club in 1895, and one of the greatest sportsmen I ever met. As the number of members was strictly limited to 250, it was difficult to get admission and the committee had power to admit only those it chose. In one word, it was the nursery of French lawn tennis. A player of the Tennis Club de Paris could easily be recognised by his free style and the execution of his strokes.

There I really advanced, playing on wood all the winter. Carefully watching such good players as these mentioned above, I, involuntarily and little by little, modelled my style on theirs and made rapid advance. At the handicap meeting of the Racing Club, in the spring of 1909, I was on the -40 mark and I got to the semi-final of this event, losing against a +15.3-6 player, amongst a field of sixty-four players. That year I won my first leg on the Houlgate Cup, beating in the final my excellent friend Colin Wyllie, of Queen’s Club, whose famous forehand drive was always a terror for any of his opponents. I played consistently all the summer and when I got back to the wooden floor in autumn, I decided to train seriously throughout the coming winter.

The difficulties for so doing were great for me. I was a student in another school preparing for my engineer’s examination. Only on Sundays had I a chance to play, and of course in the different holidays during the year. But nearly every day I managed to leave the school. We were supposed to have lunch at noon. I rushed to the dining-room as soon as possible, and in less than ten minutes finished my meal. I had to catch a train on the Paris Inner Circle Railway which brought me, in less than a quarter of an hour, to Auteuil; a run to the covered courts, and I could be on the court by 12.40, where the professional of the club, the late Leonard E. Ware, an excellent player, was ready waiting for me.

As I had to be back at my school by 1.30, you can easily imagine that during the play I had one eye on the ball and the other on the clock. To save time, I changed my shoes, but not my clothing. Pardon me for giving all these details, but this is really how I improved my tennis. Most people believe I am a natural player, who always had a style and the strokes, but nothing is further from the facts. Nearly every day for months did I have this little half-hour practice with Ware. I was also at that time – and this helped me a great deal – interested in reading all the new books on the game. One of the first that I read, handed to me by Mr Masson, was Lawrence and Reginald Doherty’s book on lawn tennis. Then I went through the books of several other writers on the game, and Decugis’s when it was published later on.

Mentally, I learnt the game by forming for myself my own conception of it, but I learnt the actual strokes with Ware in those very short practice bouts that I had three or four times a week. We were never satisfied, and after practising the most important shots, fore- and backhand drives, we continued through all the range of volleys, then the service, then the smash, the lobs and every form of stroke. By this constant mental as well as physical training I gradually evolved the strokes and execution which have combined to form my style.

On Sundays I played games with my friends, and very rapidly did the best players of the club accept me in their fours. That year, 1910, I beat, during our Easter meeting, Gordon Lowe, and this was my first international victory. I then entered, the week after, in the Queen’s Club meeting for the first time, and Gordon Lowe took his revenge by beating me in the fifth set and actually won the title. It was for me the first tournament of what I would call my English Tour.

I stayed in England three months in succession, and played in eleven tournaments. This was my first trial on grass, and of course I could not expect to win anything, and did not. But I mention this trip because I really think it gave my game that necessary touch that nobody can acquire without playing on grass. I was, when I landed in England, frightfully unsteady. When I left, I had understood the value of steadiness, and though I could not actually, in such a short time, change my game and the conception of it which I had forged in my brain in the course of years, it certainly did me a tremendous amount of good to get beaten, time and again, by men whom I thought I could beat.

On my return home, I immediately felt the benefit of my recent experiences, on grass, and nearly succeeded in beating my friend Decugis, who was at that time one of the very best players on the Continent. I really think my trip round the London tournaments made me understand many sides of the game different to those I had been made to cultivate. I understood the right value of steadiness; I understood that tennis not only resided in the execution of strokes, but that in the brain lies, in many cases, more than half the job.

The English turf did not allow my arm to hit the ball as freely as my Paris wooden and hard courts, so I had to find something else. I had also the advantage of playing some double games with such a magnificent teacher as Leslie Poidevin, a man who knew perfectly well what the word placement meant. His style of play was very much like Randolph Lycett’s, especially his low drive on the return of the service and his stance on the court. He explained to me that the two great principles in doubles are: (a) to send the ball over the net once more often than your opponent; and (b) that in most cases the best and safest placement was between the two opposite players. So simple, but so true. During all the winter 1910-1911, I never forgot, during my practice games with Ware or with my friends, what the English turf had taught me.

The year 1911 was for me a most successful one, and I won the French National title (covered and hard courts) for the first time; I succeeded also at Queen’s (covered courts), in Rome, Brussels, at Wimbledon, where I won the doubles with Max Decugis, and I represented my country in many inter-national competitions.

In October 1912, I entered the army as a gunner, but beforehand I perhaps had a record as good as in the previous year, retaining my title at Queen's in a hard- fought five-set match with Antony Wilding, winning two gold medals in the Olympic competition (covered courts), and reaching the final of the all-comers’ at Wimbledon, when your wonderful player and fighter, Arthur Gore, gave me again a sound beating.

After the War life had very much changed for everyone, and I never felt I played the same tennis as before; and if, occasionally, I managed to get through some competition, I don’t think I ever did it with the same physical fitness, the same confidence, or the same quality of play as in old times. Seven years off the court is too great an interval, and the great strain on the brain as well as the nerves, of the War, has proved, time and again, a heavy handicap which I could not overcome.

1909 - 1926

26

220

163

1922 - British Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1921 - French International Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1921 - British Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1920 - French International Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1920 - French Closed Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1920 - French National Championships (Open)

1920 - British Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1919 - Coupe Albert Canet (Amateur)

1919 - World Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1919 - Deauville (Open)

1919 - Houlgate (Amateur)

1919 - Cabourg (Amateur)

1919 - Inter-Allied Tournament (Amateur)

1919 - French International Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1913 - French International Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1912 - French International Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1912 - Coupe Albert Canet (Amateur)

1912 - French Closed Covered Court Championships (Amateur)

1912 - Olympics Indoor (Olympic Games)

1911 - Dieppe (Amateur)

1911 - French National Championships (Open)

1911 - Paris International Championships (Open)

1911 - Houlgate (Amateur)

1910 - Wimbledon Plate (Consolation) (Open)

1910 - Cabourg (Amateur)

1909 - Cabourg (Amateur)

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Douglas Powell

2-6

6-3

6-0

6-3

Round 2

Christiaan (Kick) van Lennep 1 *

André Gobert

2-6

7-5

7-5

8-6

Round 1

Ram Jagmohan 1 *

André Gobert

w.o.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Henri Reynaud

6-1

6-2

3-6

6-3

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Henri Landry

5-7

6-3

6-2

6-1

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Patrick Spence

0-6

9-7

6-2

6-3

Quarterfinals

Sydney Jacob 1 *

André Gobert

2-6

2-6

6-4

7-5

Retired

Round 1

Round 2

Denys Hippolyte Marie Laurent 1 *

André Gobert

6-8

6-0

4-5

ret.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Roger George

3-6

6-4

6-0

6-2

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Jean Borotra

7-5

12-10

2-6

1-6

6-4

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Marcus Wallenberg

7-5

1-6

7-5

7-5

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jean Augustin

6-3

6-1

6-4

Final

Rene Lacoste 1 *

André Gobert

3-6

6-1

6-1

3-6

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

J. d' Espine

8-6

4-6

6-3

6-3

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Umberto de Morpurgo

7-9

6-3

11-9

1-6

6-3

Round 4

Jean Washer 1 *

André Gobert

5-7

6-4

6-4

10-8

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Neville Deed

6-2

6-1

6-0

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Rupert Wertheim

6-4

6-4

6-2

Round 3

Algernon Kingscote 1 *

André Gobert

4-6

6-4

6-2

6-2

Round 1

Round 2

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Frédéric Albert Borotra

6-3

6-0

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Albarran

6-1

6-3

Semifinals

Umberto de Morpurgo 1 *

André Gobert

7-5

6-1

Round 1

John (Brian) Gilbert 1 *

André Gobert

w.o.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

M. Chancerel

6-1

6-2

6-3

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jacques (Toto) Brugnon

6-0

6-3

6-1

Semifinals

Henri Cochet 1 *

André Gobert

1-6

9-7

6-4

6-2

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

Brian Norton

4-6

6-1

6-8

6-4

6-2

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Hirsch

6-1

10-8

6-4

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Marcel Eugène Dupont

7-5

7-5

8-6

Final

Jean Borotra 1 *

André Gobert

4-6

3-6

6-3

7-5

6-4

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

w.o.

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Francis Wordsworth (Frank) Donisthorpe

6-0

4-6

6-1

6-0

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Arthur Diemer Kool

6-3

4-6

6-1

6-4

Round 4

Cecil Campbell 1 *

André Gobert

9-7

1-6

4-6

4-2

ret.

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Leonce Aslangul

6-0

6-2

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

8-6

6-4

6-2

Round 2

Nicolae Mishu 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

11-9

6-3

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Rumeau

6-0

6-0

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

P. Ringuet

6-1

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Coutot

7-5

6-1

Final

Marcel Eugène Dupont 1 *

André Gobert

2-6

6-3

2-6

7-5

6-1

Challenge Round

Jean-Pierre (Jean) Samazeuilh 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-3

2-6

7-5

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Walter Cecil Crawley

6-2

6-4

4-6

0-6

7-5

Round 1

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Cousin

6-4

6-1

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jean Couitéas de Faucamberge

7-5

6-1

Final

Jean Borotra 1 *

André Gobert

6-1

3-6

6-3

6-4

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Percy Portlock

6-1

6-2

7-5

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Harold Scotter Owen

6-1

6-2

6-3

Round 3

Zenzo Shimidzu 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

10-8

4-6

2-6

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Dezerville

6-0

6-3

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Tuault

6-0

6-0

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Maxime Guillemot

w.o.

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jean Augustin

6-1

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-1

4-6

1-6

6-3

6-2

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

José María Alonso de Areyzaga

6-3

6-1

6-1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Arthur M. Lovibond

6-4

6-3

6-2

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Charles Winslow

7-5

7-5

7-5

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Erik Tegner

w.o.

Final

William Laurentz 1 *

André Gobert

9-7

6-2

3-6

6-2

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jacques (Toto) Brugnon

6-2

6-2

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jean-Pierre (Jean) Samazeuilh

13-11

1-6

7-5

6-3

Final

André Gobert 1 *

François Blanchy

3-6

6-1

6-2

6-3

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-3

3-6

1-6

6-2

6-3

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Frank Fisher

w.o.

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

John P. (Jack) Wendell

6-1

6-2

6-1

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

James O'Hara Murray

6-2

6-4

6-2

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Theodore Mavrogordato

6-0

6-2

6-2

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Major Josiah George Ritchie

6-3

6-1

6-1

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

Percival Davson

6-4

7-5

6-2

Semifinals

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Jacques (Toto) Brugnon

6-0

6-2

6-1

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Nicolae Mishu

6-1

6-4

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Arthur M. Lovibond

6-2

6-2

6-4

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Francis Wordsworth (Frank) Donisthorpe

10-12

6-2

6-0

6-2

Round 4

André Gobert 1 *

Rodney Heath

3-6

6-4

6-4

61

Quarterfinals

Gerald Patterson 1 *

André Gobert

10-8

6-3

6-2

Round 1

Nicolae Mishu 1 *

André Gobert

6-0

8-6

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Henri Canivet

6-1

6-0

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

William P. Rowland

6-0

6-3

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Cousin

6-0

6-0

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

P. Guillemant

6-2

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Dean Mathey

6-1

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-0

6-3

6-3

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-0

6-2

6-2

Poule

Algernon Kingscote 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

6-4

7-5

Poule

André Gobert 1 *

Percival Davson

7-5

6-4

4-6

6-4

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Georges Sabbagh

6-3

6-0

6-1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Henrik Ernst Wilhelm Fick

w.o.

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Armand Charles Simon

6-1

6-0

6-0

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Georges Manset

6-1

8-6

6-2

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-3

6-3

6-4

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Vitry

w.o.

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Haouir

6-2

6-0

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Dezerville

6-2

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

J.M. Barbas

6-3

6-3

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

3

sets

Round 1

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Dumortier

6-2

6-0

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Leonce Aslangul

6-1

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-3

6-1

6-2

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

T. Tripp

6-0

6-2

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

C. McGavin

6-3

6-1

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Frank Riseley

6-3

7-5

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-4

2-1

ret.

Round 1

Quarterfinals

Alain Gerbault 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

6-1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

André Chancerel

7-5

3-6

2-6

6-4

6-4

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

A. Georges Watson

6-2

6-1

5-7

6-1

Quarterfinals

Ludwig von Salm 1 *

André Gobert

7-5

6-3

6-3

Poule

Friedrich Wilhelm Rahe 1 *

André Gobert

6-1

6-1

6-1

Poule

Oscar Kreuzer 1 *

André Gobert

1-6

6-4

6-2

6-3

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Robert Quennessen

6-4

6-3

6-4

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Émile Chelli

6-4

6-3

6-1

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Ludwig von Salm

6-4

6-1

6-0

Final

William Laurentz 1 *

André Gobert

6-1

9-7

3-6

6-2

2-3

ret.

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-3

4-6

6-2

6-4

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

w.o.

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Mikhail Sumarokov-Elston

6-2

6-1

6-3

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Bela Von Kehrling

6-1

6-1

6-0

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Otto Froitzheim

6-3

6-3

6-3

Final

Tony Wilding 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-3

1-6

6-4

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Albert Canet

w.o.

Final

Max Decugis 1 *

André Gobert

5-7

8-6

6-0

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Dr Ernest Ulysses Williams

6-0

6-4

6-0

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

James Cecil Parke

6-3

6-4

6-4

Round 4

André Gobert 1 *

Albert Prebble

6-1

6-4

6-4

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Friedrich Wilhelm Rahe

6-1

6-2

7-5

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-3

6-3

1-6

4-6

6-4

Final

Arthur Gore 1 *

André Gobert

9-7

2-6

7-5

6-1

Round 1

A. Félix Poulin 1 *

André Gobert

w.o.

Round 1

Major Josiah George Ritchie 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

5-7

5-7

6-4

1-1

ret.

Round 1

Major Josiah George Ritchie 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

5-7

5-7

6-4

1-1

ret.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Émile Chelli

6-2

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Robert Quennessen

6-2

10-8

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Georges Gault

6-2

6-2

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

A.E. Blanc

6-2

6-2

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Germot

6-4

6-4

6-2

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

P. Renard

w.o.

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

J. Arnal

6-1

6-1

6-0

Quarterfinals

Robert Kleinschroth 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-3

6-4

Challenge Round

Max Decugis 1 *

André Gobert

w.o.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Erik Larsen

8-6

6-1

5-7

8-6

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Carl Kempe

6-1

6-2

7-5

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Arthur Lowe

6-1

6-1

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Gordon Lowe

6-4

10-8

2-6

2-6

6-2

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Charles Dixon

8-6

6-4

6-4

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-2

6-3

6-2

Poule

Arthur Gore 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

4-6

6-3

6-3

Poule

Charles Dixon 1 *

André Gobert

4-6

6-4

6-2

6-3

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

4-2

ret.

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

William Strong Cushing

6-2

6-0

7-5

Round 2

Arthur Gore 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-3

6-2

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

M. Dufau

6-1

7-5

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Craig Biddle

6-0

6-3

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Albert Canet

6-1

8-6

Final

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-4

6-4

6-3

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Dufau

6-3

6-1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Albert Canet

6-1

6-3

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-3

3-6

8-6

Semifinals

Tony Wilding 1 *

André Gobert

1-6

6-2

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

1-6

9-7

6-1

6-1

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Jacques Marie Gustave Samazeuilh

7-5

6-2

6-2

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

E. Strauss

6-4

6-2

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Max Decugis

6-3

6-1

7-5

Challenge Round

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Germot

6-1

8-6

7-5

Round 1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Clemente Serventi

6-2

6-4

6-8

7-5

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Ludwig von Salm

7-5

6-4

6-4

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Maurice Germot

11-9

6-1

ret.

Final

Max Decugis 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

6-3

6-4

Poule

Robert Auguste William Laurentz 1 *

André Gobert

3-6

6-3

4-6

6-3

6-1

Poule

André Gobert 1 *

Otto Salm

6-1

6-1

6-3

Poule

André Gobert 1 *

Curt Bergmann

6-3

5-7

10-8

6-2

Poule

Rodney Heath 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

6-4

4-5

ret.

Poule

Robert Kleinschroth 1 *

André Gobert

5-7

8-6

6-0

9-7

Round 1

Stanley Doust 1 *

André Gobert

6-2

6-2

6-1

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Arthur Murray Cooper

6-2

6-3

6-3

Round 2

Gordon Lowe 1 *

André Gobert

4-6

6-1

6-2

7-5

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

6-1

6-2

Final

Max Decugis 1 *

André Gobert

3-6

6-4

6-4

6-8

6-1

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Brame Hillyard

6-3

6-8

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Neville Willford

6-2

6-3

Round 3

Major Josiah George Ritchie 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

6-3

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

P.F. Schobloch

6-0

6-2

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

William Alfred Ingram

6-4

6-3

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Cecil Stewart Hartley

6-2

6-0

Semifinals

Theodore Mavrogordato 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-2

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Reginald Speke Barnes

1-6

6-2

6-3

7-5

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Augustus Wallace MacGregor

6-2

6-4

6-0

Quarterfinals

Gordon Lowe 1 *

André Gobert

4-6

6-1

6-2

3-6

8-6

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Alfred Richards Sawyer

8-6

9-7

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

George P. Allen

6-2

6-2

Round 3

André Gobert 1 *

George Henry Nettleton

w.o.

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Henry Pollard

6-4

7-5

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Eric Pockley

4-6

6-1

6-1

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Percival Davson

6-4

6-4

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

Cecil Stewart Hartley

6-2

6-2

Quarterfinals

André Gobert 1 *

Sidney Johnson Watts

6-3

6-2

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Philip MacDonnell Sanderson

6-4

6-1

Final

Alfred Beamish 1 *

André Gobert

6-0

6-2

Round 1

Charles Stuart Gordon-Smith 1 *

André Gobert

6-2

2-6

10-8

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Edward Stanley Franklin

5-7

6-3

6-2

Round 2

Theodore Mavrogordato 1 *

André Gobert

6-2

6-0

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Colin Charles Wyllie

6-4

6-3

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

Pierre Defize

6-2

6-3

Quarterfinals

Paul de Borman 1 *

André Gobert

6-1

6-2

Quarterfinals

Étienne Micard 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

7-5

Round 1

Albert Canet 1 *

André Gobert

11-9

3-6

6-0

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

William Laurentz

7-5

6-3

Final

Max Decugis 1 *

André Gobert

6-3

6-0

6-4

Quarterfinals

Jean-Pierre (Jean) Samazeuilh 1 *

André Gobert

w.o.

Semifinals

André Gobert 1 *

Mr. Curlier

6-3

7-5

Final

André Gobert 1 *

Colin Charles Wyllie

?

Round 1

André Gobert 1 *

André Jousselin

6-4

6-1

Round 2

André Gobert 1 *

P. Guillemant

6-4

2-6

6-4

Quarterfinals

Maurice Germot 1 *

André Gobert

6-4

9-7